Did Proto-Indo-European, or any reconstructed language for that matter, really exist? Of course it did, linguists say so! But do you know how were they able to know that? Humm! No worries, this is what this article is all about.

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is estimated to have existed as a living language from 4,500 B.C.E. to 2,500 B.C.E, but was extinct ever since. People did not even know that this language ever existed. It’s only during the 19th century that linguists were able to reconstruct this language. The linguistic reconstruction was possible following pretty amazing techniques that were made available by the comparative method.

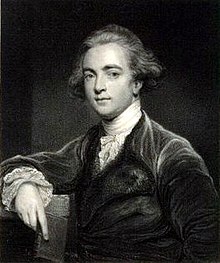

The reconstruction of PIE started with this guy:

Sir William Jones.

He was a British lawyer and hyperpolyglot who spoke as much as 30 languages with varying degrees of proficiency. He was born in 1746. During this time people believed that the similarity between languages was due to inter-lingual borrowings: English and French are similar because they borrow from each other, or maybe they share the same root as the case with Romance languages. This made sense because languages that were geographically closer were similar, and those which were distant were different because they didn’t borrow much from each other, like English and Arabic. Our guy Sir William Jones too had had this belief until he was sent to India in 1783. India was under British occupation during this time.

In India, there is a language called Sanskrit, it served similar purposes to Latin and Greek in Medieval Europe; only few people used it as their first language but it was used exclusively for legal and religious purposes. Similar to Latin, it was an ancestor to a large number of languages spoken in India. The languages that hail from Sanskrit are called Indo-Aryan:

(languages in red are not used anymore)

Jones was obligated to learn some Sanskrit to do law in India. It’s just another language and he knew dozens already. When he started learning it, he was awe-struck. He started noticing things about this language, things that seemed insanely familiar. He found out that the word for ‘mother’ is mātr, similar to Latin’s mater (from which English maternal and maternity is derived).Coincidence? Let’s see. The word for ‘father’ is pitr, again similar to Latin’s pater (the root for paternal in English), vir in Latin is similar to Sanskrit vira.

The idea that Sanskrit borrows from Latin, or vice versa, doesn’t make sense and can’t explain the similarity between he two. There is a whole lot of real estate between Europe and India, and they hadn’t had enough contact to account for the similarities. There was something going on, something really strange.

Let’s stretch our ‘logic’ muscles here. Spanish and French have similarities because they both come from Latin. Marathi and Hindi are similar because they both come from Sanskrit. So, maybe, just maybe, Sanskrit and Latin (Greek, too) have similarities because they share some sort of a common root that extended beyond their respective continents.

Right after these discoveries, Jones said in 1783 some words that will be forever remembered in the history of linguistics:

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.

Sir William Jones

This issued linguistics as we know it today. This also issued a frenzy in philology. People were particularly concerned about trying to find answers to questions such as: which language belonged to which family? Which didn’t belong to a certain family? Why such languages belong to this family and not others? How do we tell that this language belongs to this family and this to that? They needed answers, answers that couldn’t be found for the next few decades. Then came along Jacob Grimm, and founded Grimm’s law.

Jacob Grimm was preoccupied with looking through huge numbers of dictionaries, a nerdy thing of course but very important to popular culture. His purpose behind looking into dictionaries was to find patterns that exist among languages, particularly between German and other languages. Here is something he found out:

German: Vater (pronounced “fater”)

English: father

Dutch: vader (pronounced “fader”)

Swedish: fader

Latin: pater

Greek: pateras

Sanskrit: pitr

Persian: pedar

All the words for ‘father’ started with ‘p’ except for very few languages spoken in Northern Europe, whose words for ‘father’ started with ‘f’. These exceptions are not a coincidence, however. Consider the word ‘foot’:

German: Fuß

English: foot

Dutch: voet

Danish: fod

Swedish: fot

Ancient Greek: poús, podós

Latin: pēs, pedis

Sanskrit: pāda

Latvian pēda

A pattern emerged here. Where these languages have ‘f’ others have ‘p’ and vice versa. It’s not just the ‘f’ ‘p’ pattern that has been noted, other patterns also exist. For example, ‘k’ where other languages have ‘h’ (e.g. ‘canine’ and ‘hound’), ‘t’ where other languages have ‘th’ (e.g. ‘thou’ and ‘tu’), etc. It’s patterns like these that led Grimm to establish his law. In the IPA, Grimm’s law is formulated as follows (technical on the left, nontechnical, though less accurate, on the right)

bʰ > b > p > ɸ bh > b > p > f

dʰ > d > t > θ dh > d > t > th

gʰ > g > k > x gh > g > k > kh

gʷʰ > gʷ > kʷ > xʷ gwh > gw > kw > khw

Grimm’s law’s import is that the established patterns of change that are shared by certain languages ought to mean that they come from a single root language which itself descended from en even older root language.

As he unraveled these patterns, Grimm became a pioneer in the comparative method. Many mysteries were resolved. Now we not only know which language belongs to which family, but also how close languages are to one another, based on sound changes. A real piece of the puzzle was able to be found, and full the image was now being constructed from this single piece.

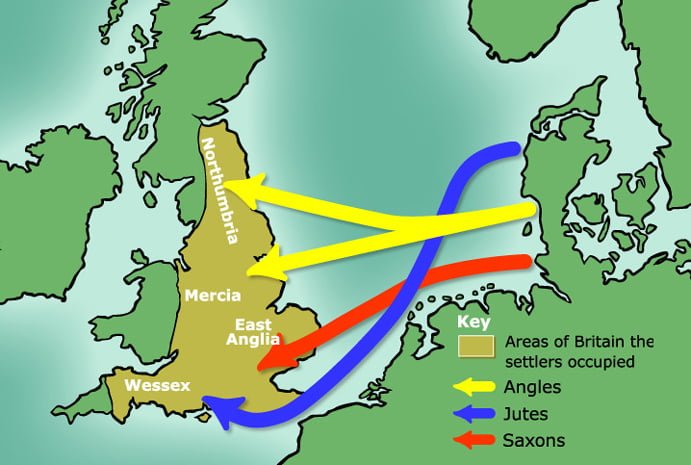

English, German, Dutch, Icelandic, the Scandinavian languages, among others, were found to belong to the general family of Germanic Languages.

Let’s now return to Indo-European. Since the languages belonging to this family were found mainly in India and Europe, the name Indo-European was chosen, and the language was called Proto-Indo-European. It’s a pretty easy concept to grasp, even if you’ve never did Historical Linguistics. Let me illustrate. Consider the Germanic word for ‘dog’. In German, it’s Hund, Dutch hond, English, well, ‘dog’, and Swedish hund. Since English also has ‘hound’, it is safe to assume that the Proto-Germanic word for ‘dog’ was hund.

Case endings is another interesting indicator of language-relatedness. Gothic, an ancient and now extinct language, is an important source that helped immensely in reconstructing Proto-Germanic. It was important for two reasons: (1) it didn’t undergo a number of sound changes found in other Germanic languages. (2) and this is more important, there are remains of this language, mainly the Gothic Bible, which predates anything written in any other Germanic language by hundreds of years, and which we can use as a resource.

In Gothic, nouns that bear nominative masculine singular case often ended in -s. Modern Germanic languages, however, dropped this this case ending system, with the exception of Icelandic in which the case endings survived. In Icelandic, nominative masculine singular nouns end in -r. Gothic -s and Icelandic -r are not arbitrary but related. The relatedness can be explained, once again, by sound change. Germanic Languages underwent a sound change called rhotacism in which /s/ or /z/ changed into /r/. Gothic retained the /s/ because it died before that happened. Example of rhotacism in English include: ‘stronger and strongest’, ‘more’ and ‘most’, and ‘was‘ and ‘were’.

A large number of Indo-European languages show this particular detail in which nouns with nominative masculine singular case ended in -s (e.g. Latin –us, Greek –os, etc.). Based on data like this, we would safely assume, with a certain degree of exactitude, that Proto-Germanic had something similar (i.e. many words ended with –uz, -az, or -iz). Considering this, the Proto-Germanic word for ‘dog’ could have been something like *hundaz (asterisk means the word is reconstructed).

Now what could have been the word for ‘dog’ in Proto-Indo-European? Well, we have canis in Latin, κύων kyon in Greek, ci (pl. cwn) in Welsh, qen in Albanian, *hundaz too (remember Grimm’s k > h) and there you have it! The Proto-Indo-European root was something like *kwon. We can’t say for certain it was identical to this, but we can only go as far as existing data allows, and there are many variations, but the evidence points to the *kwon direction.

Our methods can also make us go so far as to figure out where exactly Proto-Indo-European was spoken. We can use linguistic clues such as the PIE word for ‘honey’ (*médʰu), “beech tree” (*bʰehgos), to reach the conclusion that PIE was spoken just east of Ukraine, approximately 8000 years ago, with very little margin for error.

Our methods can allow us to do more than just that. We can reconstruct even older languages, and we know exactly what languages belong to which family, and we can group more families together. Just look at what we were able to do:

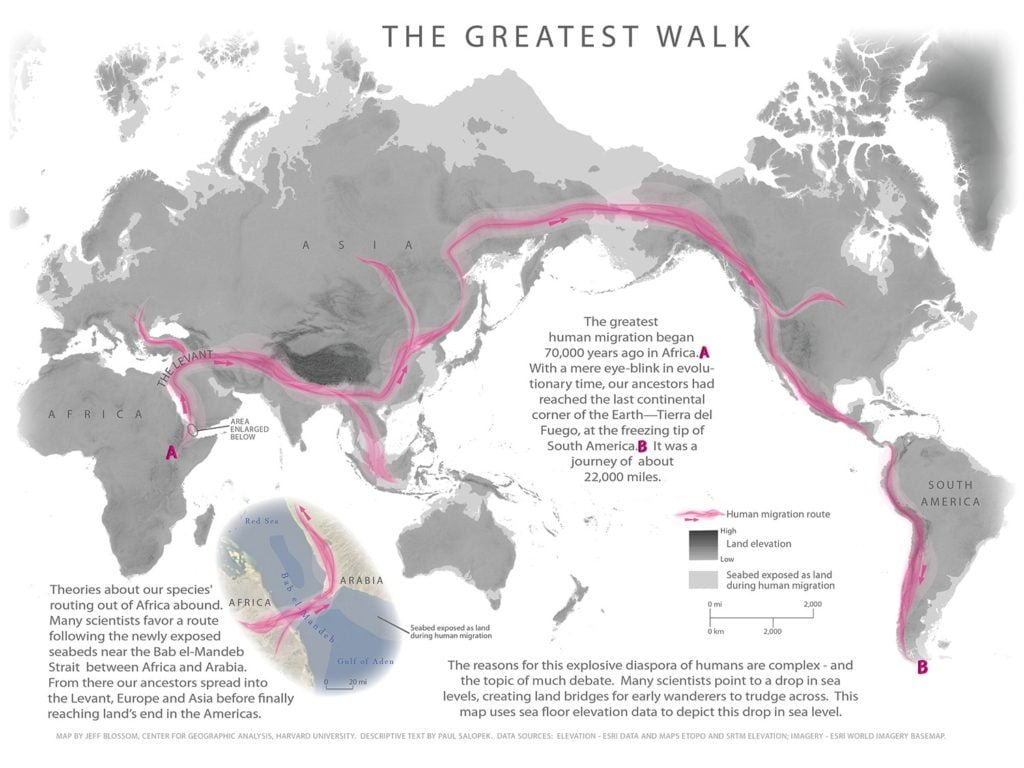

This allowed us to speculate on the mother of all languages, Proto-Word, it surely must have existed but we don’t know exactly what it looked like. It is believed to have existed between 100,000 to 200,000 years ago. These findings and others started with a curious man who looked at things differently.

Please share the article if you think it deserves. Looking forward to seeing you in my next article.

Those who know nothing of foreign languages know nothing of their own.

Johann Wolfgang Goethe