Tracking the etymology and history of words is a fun exercise. This exercise gets even funnier when you realize that such very common words have weird etymologies. In this article, I am going to draw your attention to probably the most used noun in the English language. Ladies and gentlemen, meet the peculiar etymology of a very peculiar word: ‘thing’. I would describe the etymology of ‘thing’ to be hilariously pathetic as would you when you read the whole story behind the word.

Thing, as such, first appeared as the Proto-Indo-European root *tenkó-, and it roughly meant “span” or “extend”. This root stretches probably far back to the possible ancestor *tenk-, which meant “to suit” or “to fit”. There is good reason to believe that this root (i.e. *tenk-) is related to another root *ten- which is regarded as the ultimate root of the Latin tempus meaning “time”.

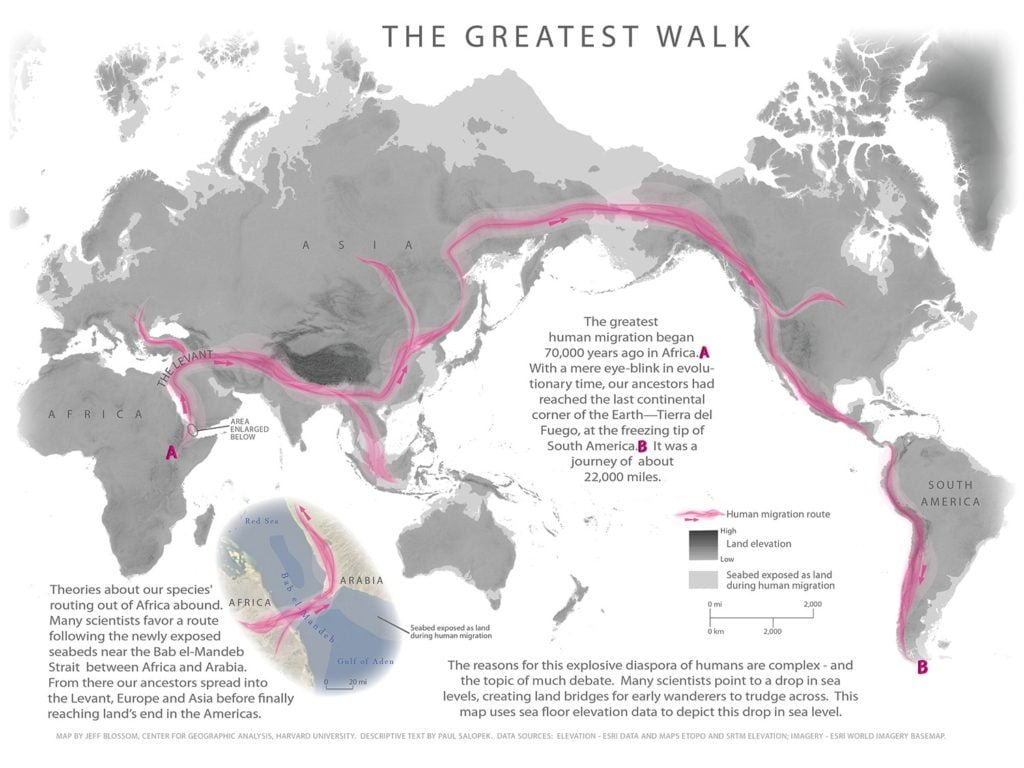

Proto-Indo-European speakers split apart, due to travel and trade reasons, and so were scattered into multiple groups which eventually resulted in their languages splitting apart as well. One group pushed their way into Greece and Italy, and this gave us Latin and Greek. Another wandered to India, which gave us Sanskrit. Then another group settled in Scandinavia whose dialect became what is called the Proto-Germanic Language.

The Germanic languages (i.e. English, German, Dutch Danish, Swedish, Icelandic, Norwegian, and Faroese) do not come from German, but from a language called Proto-Germanic, a language spoken around the late Classical Era. Here is the distribution of these languages in Europe, where Netherlandic is another term for Dutch:

Now, what does this have to do with the word thing? Well, some of these languages picked up our root, *tenkó- from their ancestor Proto-Germanic and improved on it, and thus had been updated to pronounce as þingą (where the letter “þ” stands for the “th” sound.) þingą meant “meeting”, “appointment”, “assembly”, or “parliament”. This meaning is still retained in Norwegian as a term for the Norwegian parliament, the Storting, which means “great parliament”, but could also be translated as “big thing”.

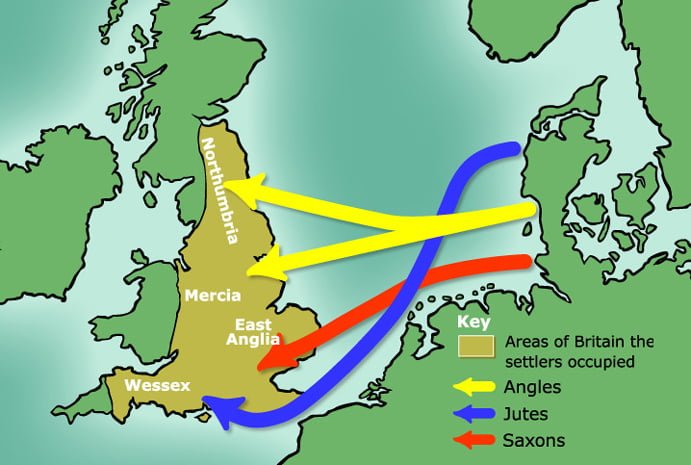

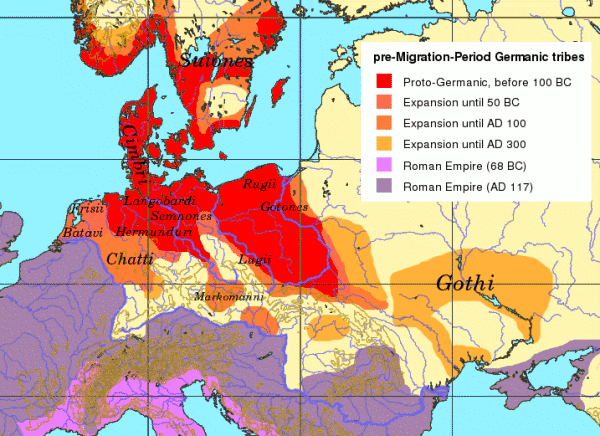

So when you want to attend a meeting, it’s because you want to talk about something, right? a “matter” or an “issue”! So þingą referred to the meeting as well as the thing that was discussed there. Now we’re getting somewhere, huh! Now what happened with the Indo-Europeans before them, also happened with the Germanic people; they started to migrate and split apart. One group went to the north and they gave us the Norse, another went to the east and they identified as the Goths, and a third group migrated to the west and became the West Germanic tribes. This is summed in the following map:

Germanic Migration Age. Source: Wikimedia

As the Roman empire started to shrink in power, the Roman armies at then Brittania retreated and left the Celts

During this time, new alternations were introduced to the word þingą, the final vowel had been dropped, and it was now þing in Old English. Furthermore, it did not fully retain its meaning, it had diverged ever slightly more: while it kept referring to “meeting” or “matter” it has focalized more on what the “issue” was about, that is, any matter or any object. It’s around this time that sum þing, naþing, and aniþing first appeared.

Another shift was brought by the Normans, changing Old English to Middle English. Under the French influence, þing had become thing, and new denotations were introduced to the word as well: it referred not to a defined, particular “matter” but more or less to anything made out of matter. It is in the Middle English era, circa 1400, that the word everything first appears.

Now, in the following centuries, thing rid itself of all its other meanings, retaining one heavily genericized meaning, the one which it currently has today, giving poor semanticists such a hard time to define the word:

Source: Oxford Dictionaries.

So now thing could refer to anything from as small as bacteria to as big as the cosmos and everything in between. It could also refer to something as weird as your balls or butt so that it sounds like something euphemistically desirable.

The fate that this poor word had to suffer is hilariously pathetic, don’t you think? It originally had a very specific meaning before becoming literally the most generic word in the English language.