Linguistics as a field of study flourished tremendously beyond the hopes of its founders. Modern linguistics started a cognitive revolution in the 1950s and has been extending ever since. Thanks to linguistics we know so much more about human languages than ever before, from their origins, why are there so many of them, and how to use language to solve crimes. Not only that, linguistics gave us pretty compelling insights into the nature of the human mind, how to build talking machines, how to train people with dyslexia so they can read, how to repair brain functions that pertain to language, etc. It is an impressive feat. But despite these advancements, there are still many unsolved problems in linguistics.

There is only one very big problem: the main language mysteries that linguistics set out to unravel are still as mysterious as ever before. Many fundamental problems to linguistics are still unsolved. You’d be surprised to know how little we know about central issues in the study of language. That’s what this whole article is about. So, let’s go through these unsolved problems:

The language faculty:

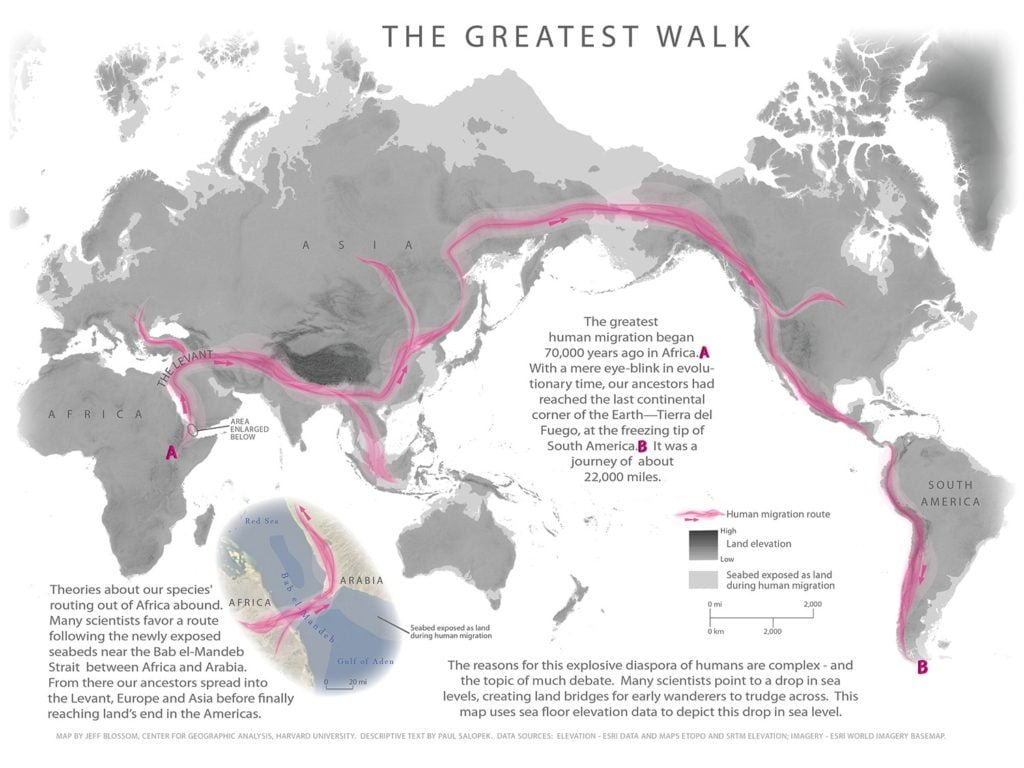

Our ability to learn languages is by far the most defining human property. But we know so little about this ability; we don’t know what exactly distinguishes human language from other communication systems found in other species. Humans’ closest relatives, such as gorillas and chimps, have demonstrated a remarkable ability to learn and use sign language. In a meticulously designed experiment, Koko the Gorilla, throughout the years, was able to learn hundreds of signs and learned to combine many of them into phrases. A book that details all the stages of this experiment can be found [here].

Bird-songs and birds’ ability to acquire and use certain calls have been shown to demonstrate remarkable syntactic properties as well. A fascinating scientific article that expounds this ability can be found [here]. Parrots show an interesting ability to pronounce a wide variety of human sounds. Bees and their dances are also something interesting from a linguistic point of view. If the animal kingdom is abundant with communication systems that are comparable in some way to that of humans, then the difference between our language faculty and that of other species is only qualitative. The question that linguists are struggling with is: What distinguishes human language from other animals’ communication systems?

Another question is: How special is language? Are there aspects of language that are completely unique and encapsulated (distinct) from the rest of our cognitive system, or is language ultimately just a special combination of a lot of domain-general functionality that humans already possess? We don’t really know.

Language learning:

How do adults learn language is a toughie! Obviously, the question of how babies learn language is paramount, but how adults learn a 2nd or a 3rd language is also an intriguing puzzle. Do they use the same, diminished, mechanisms as babies or do they learn language differently? What are some predictors of adults’ language learning success?

What is fluency? Fluency is a fundamental concept in linguistics, underlying a lot of assumptions, but I don’t think there is a clear operational definition. We say things like, “any baby can become fluent in any language,” or “children are fluent in their native language by the time they’re 5,” and so on, without a clear definition of what fluency means.

Modeling and measuring language:

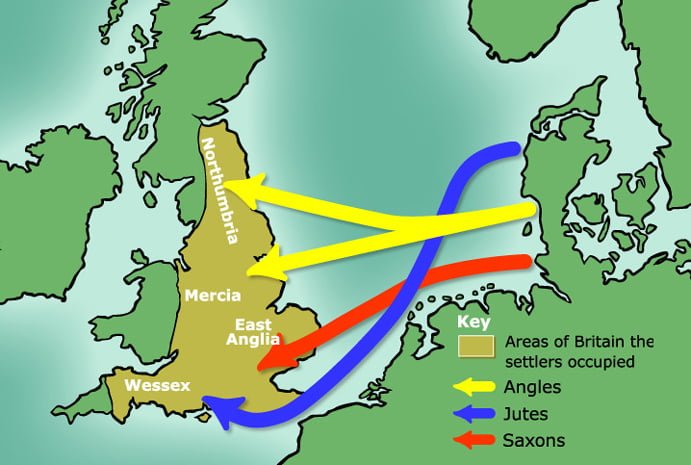

What is the optimal model for reconstructing languages phylogenetically? There is still a lot of debate on how language relationships (oftentimes modeled as trees) should best be constructed given that there are things in language that don’t really exist in evolutionary biology (the source of linguistic trees), like language contact, borrowing, and so on. Associating time with trees is also a big puzzle underlying controversies such as the age of Indo-European.

How can we measure language complexity? Again, a key concept in linguistics, but without a clear operational definition, prevents us from answering whether some languages are more complex than others. Attempts to do so (e.g., J Nichols) are a great step forward, but clearly far short of an all-encompassing definition.

Language in context:

What are the interactions between language, culture and thought? This one is a toughie. This is partly encapsulated by the Sapir-Worph hypothesis, but I think the question is much bigger than that. How does language influence culture? Can culture then influence thought? How do the three interact?

Language and the brain:

This is probably the biggest area in which linguistics is lacking. The “what is going on in the brain during language?” is quite broad and can be broken out into more detailed questions such as:

How is language lateralized in the brain? How do the left and right hemispheres interact during language production and comprehension? Is there massive redundancy so that people can recover from a stroke by re-lateralizing these functions?

How do we recognize words? How do we go from an acoustic signal to a word, especially given how impoverished the acoustic signal often is? What are the respective functions of the dorsal and ventral processing streams in the brain?

What is the function of Broca’s area? Is Broca’s area really specific to syntax and more specifically, syntactic movement, or does Broca’s area have a more general cognitive function?

How modular are the respective parts of the brain that have been associated with different functions? Previous research has suggested that certain parts of the brain are associated with things like speaking, word recognition, top-down effects in speech processing, syntax, phonology, processing emotional affect in language, and so on. How do these different regions interact, and how modular are they in terms of doing their “tasks”?

These seem to be very simple questions, but their answers are very difficult and they challenge modern science and technology. Who knows, maybe as you are reading this you’d take a challenge and embark on some research and answer some of these questions, you never know! The future of linguistics is powered by passionate people like you and me. With the right tools, we can do wonders. So don’t let that language passion die within you. Carry the torch with an iron fist and pass it on to iron fists.